Simon Jones Murphy, an entrepreneur, investor and lumberman, played an important role in the economic development of the state and helped to add four large and attractive structures to what is now the Detroit Financial District Historical area. So far as I know, all are in use as office buildings. Born in 1815 in Maine, Mr. Murphy grew up in that state and successfully invested in the timber industry there. Maine’s forests, similar to those in Michigan were primarily pine. About the time of the Civil War, Murphy realized that much of the valuable timber of the Pine Tree State had been harvested and that his financial prospects might be brighter elsewhere. In 1866, he moved his family from Bangor, Maine to Detroit where he spent the next 49 years of his long life. Presumably, he knew about the white pine forests that covered much of the Lower Peninsula and saw the potential for amassing great wealth.

Shortly after arrival in Detroit, he established a lumber firm with two partners, Mr. Eddy and Mr. Avery. Between the late 1860s and the 1890s they purchased several hundred thousands of acres of land in the Lower Peninsula so that they might cut the timber. A major challenge they faced was getti ng the huge trees out of the Michigan forests and then to mills and finally sending their products to the manufacturing firms that needed their wood. For this reason, many of the early investors in Michigan’s prosperous timber industry also were involved in building railroads and organizing Great Lakes steamship lines. At that time, much of Michigan was swampy and there were no paved roads and few railroads ran into the state’s forests. White pine trees were valuable but it was a costly proposition to cut them and then get them to where they would be useful. By the mid- to late-1880s, rail lines minimized some of those problems.

ng the huge trees out of the Michigan forests and then to mills and finally sending their products to the manufacturing firms that needed their wood. For this reason, many of the early investors in Michigan’s prosperous timber industry also were involved in building railroads and organizing Great Lakes steamship lines. At that time, much of Michigan was swampy and there were no paved roads and few railroads ran into the state’s forests. White pine trees were valuable but it was a costly proposition to cut them and then get them to where they would be useful. By the mid- to late-1880s, rail lines minimized some of those problems.

Simon Jones Murphy prospered. He realized that Detroit was a booming industrial city because of the many manufacturing firms here that used lumber from the state and iron and steel produced in Detroit. As Detroit's manufacturing industries grew, there was a need for both office structures and buildings for manufacturing.

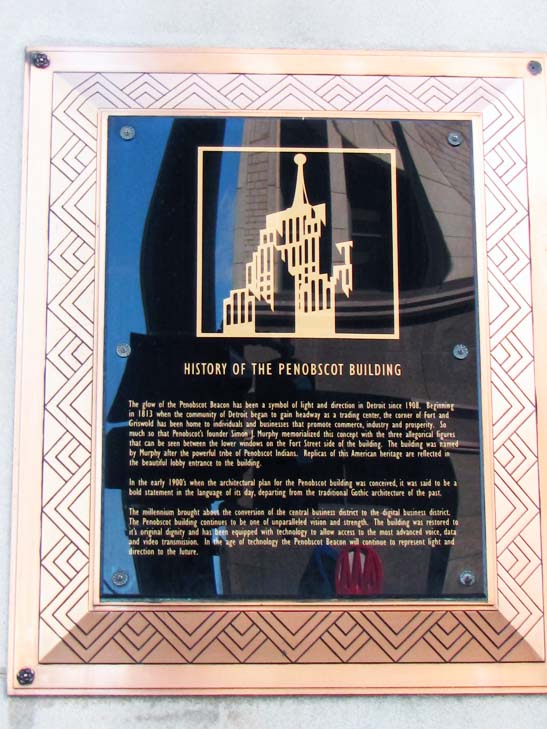

The first Penobscot Building was completed in 1905, the year that Simon Jones Murphy died. It is a 13-story office tower in brick and terra cotta with extensive limestone trim. There are five bays on the Fort Street front with five pairs of double hung windows above them. There are impressive Corinthian Columns between the eleventh and twelfth floors. Among the original tenants were the Detroit Savings Bank and the Detroit Trust Company.

The success of the first Penobscot led William Murphy—the son of Simon Jones—to erect a second Penobscot Building that may be called the New Penobscot Building, using the same architects. This one is much larger since it includes twenty-four floors of office and retail space. The first five floors are faced in gray granite, while the upper floors are faced in terra cotta and ashlar. A prominent band of terra cotta separates the uppermost four floors from the lower stories. Unglazed terra cotta became popular in England and was frequently used on the exterior of Victorian era buildings. Its use in the United States began in the following decade and had the advantage of being inexpensive and light. The first two Penobscots had adjoining rears. An alley separates them but some of the floors are connected.

The success of the first two Penobscot buildings led to the construction of the Greater Penobscot Building on the same block. This one is much larger than either of the earlier Penobscots. It is a 47-story structure with a steel frame and a granite and terra cotta exterior. The lower six floors are square but the upper floors are in the shape of an H. The building begins to taper at the 30th floor. A series of tapers means that the floors get smaller at they go up. The building is topped by a tower and at the top of that tower is an orb with a twelve foot diameter.

At 557 feet this was the tallest building in Detroit when it was completed and the eighth tallest in the world. It was then the tallest structure in the United States outside of New York and Chicago. Now Detroit has two buildings taller than the Greater Penobscot; the Renaissance Center and the Philip Johnson’s Comerica Bank Building on Woodward.

When the forest of Michigan were no longer supplying white pine, Simon Murphy purchased land in Wisconsin to continue the family business. His oldest son, Simon Jones Murphy Jr., led the firm in that state. He was also elected mayor of Green Bay where he served from 1899 to 1901.

The Greater Penobscot is one of the few buildings in Detroit where you see swastikas carved into the facing. They are highly visible on either side of the statue of the Indian above the prominent entrance on Griswold. In the early 1900s, American archeologists found that Native Americans widely used the swastika as a symbol. Why is this structure the Penobscot Building? As a youth in Maine, Simon Jones Murphy played along the banks of the Penobscot River. He may have also cut timber in the region along the Penobscot; a river that the British claimed should be the southern boundary of New Brunswick leading to the never-fought Aroostook War. The Penobscot Tribe was a well-known tribe when Murphy was in business in Maine and this explains his choice of a name for the building. The Penobscot tribe now has a reservation along the banks of the Penobscot. I do not know if the statue of the large Indian above the entryway to the Greater Penobscot bears any symbols of this tribe. But to the right and left of that statue you will see swastikas carved into the stone.

For the record, the use of the swastika in Germany has a different history. Hindus often used the swastika as a symbol meaning “It is good.” The National Socialist Party, in 1920, adopted the swastika as one of their symbols. When Adolph Hitler came to power in Berlin in 1933, he added the swastika to the flag of the National Socialist Party. Later, he adopted that flag as the nation’s flag, a decision that was later overturned.

Prior to its use in Germany, the swastika or some variant of the swastika was used with some frequency in the United States, perhaps in an effort to remind us of the native peoples. Kenneth Crittenden founded the K-R-I-T Motor Car Company in 1909. The firm changed hands in 1911 but produced cars until the start of World War I, using a building on East Grand Boulevard near the present Packard Plant. Mr. Crittenden selected the swastika as his company logo and displayed in on the radiators that were a prominent feature of his and almost all other cars manufactured in that era.

When the Renaissance Center was built, skeptics believed that it would put many of the other office buildings in downtown Detroit out of business. Supposedly, there would be few firms willing to move to the Ren Center so they would have to cut rents and that would draw firms that were renting in the Guardian Building, the Penobscot Building and a dozen or so other major office buildings. For quite a few years, occupancy rates were relatively low for office buildings in Detroit but that has turned around in recent years. The Penobscot Building and many other similar structures seem to have a reasonably good future. The opening of the Renaissance Center, in the long run, did not destroy demand for office space in other downtown buildings.

Architect for original Penobscot Building: John Donaldson and Henry Meier

Date of construction: 1905

Architect for next major addition: John Donaldson and Henry Meier

Date of construction of first major addition: 1916

Architect for most imposing Penobscot Building facing Griswold Street:

Writ Rowland employed by Smith, Hinchman and Grylls

Date of most recent major addition: 1928

Architectural style for Writ Rowland’s building: Art Deco influence incorporated into an H plan allowing light into many or all offices.

Use in 2014: Major Office Building

City of Detroit Local Historic District: Not listed

Michigan State Registry of Historic Sites: Not listed

National Register of Historic Sites: The Penobscot Buildings are included within the Detroit Historic Financial District, listed December 24, 2011.

Photograph: Andrew Chandler; July, 2004

Description prepared: January, 2014

Return to Office and Commercial Buildings